Photo credits @David Seradell

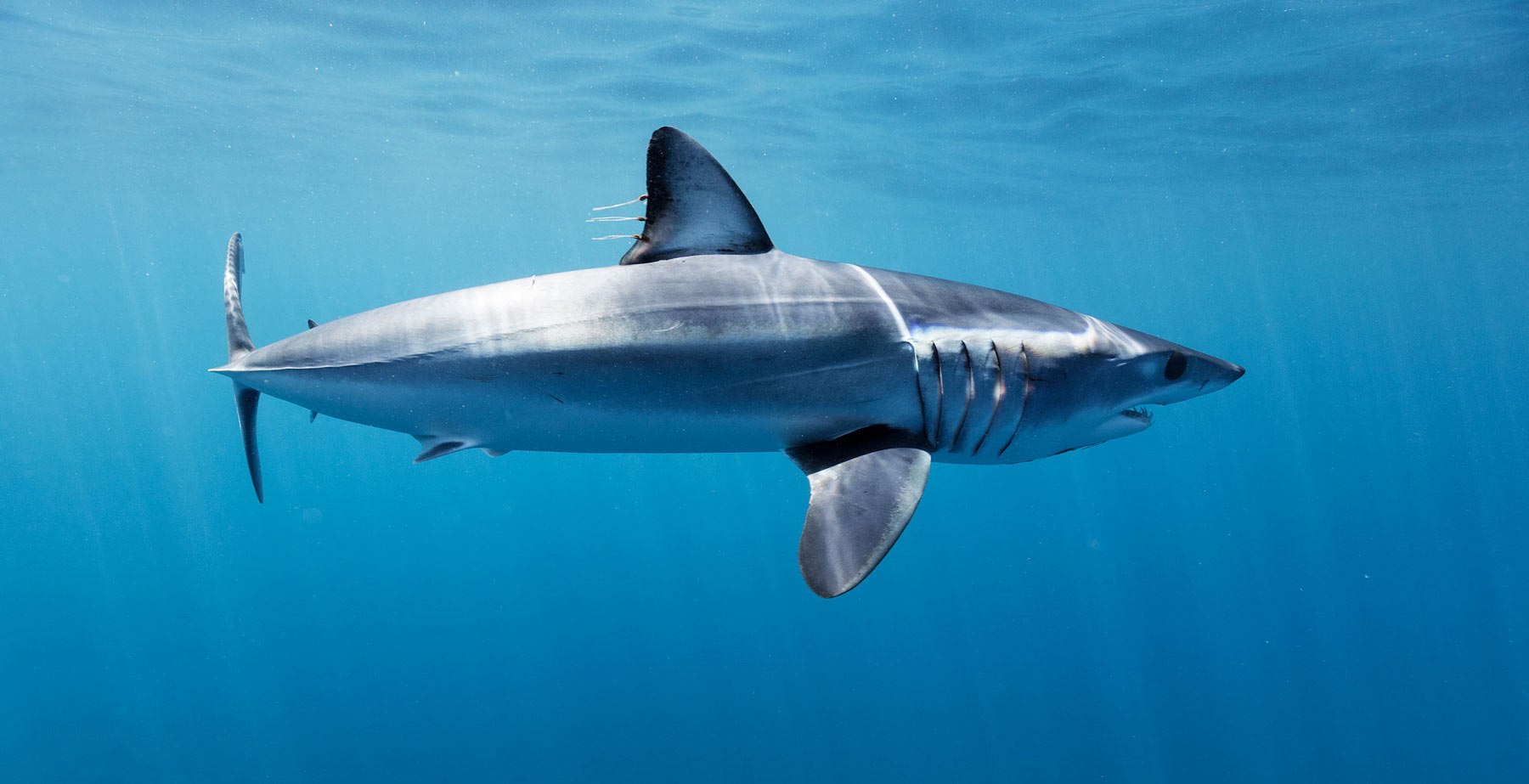

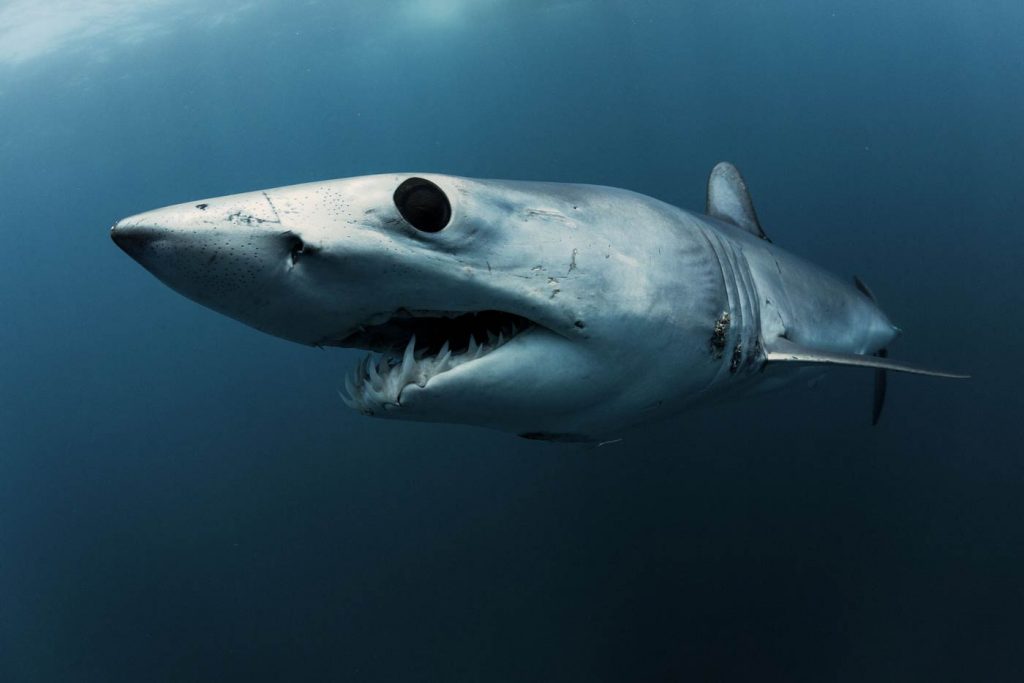

When most people think about the ultimate marine predator experience, they think of the Great White shark. But one of its smaller cousins, the Shortfin Mako shark (Isurus Oxyrinchus), also makes for an exhilarating and unforgettable encounter.

Shaped like a missile, Shortfin Mako sharks are the fastest shark in the world, capable of reaching speeds of up to 40mph. Makos may not be as big as great white sharks, but they can still grow up to a sizable 4.5 meters. However, despite their fearsome appearance reinforced by their unmistakable jaws with sharp protruding teeth, they are not aggressive to humans. Their vivacious, curious nature makes them fantastic animals to share the water with. To see them swim in their natural habitat, with their big dark eyes and silvery blue skin, is an experience that will leave you in total admiration.

Mako Shark : An Endangered Species

Mako sharks grow and reproduce slowly. To give you an idea, a female shortfin Mako shark is estimated to reach sexual maturity at around 18 years, giving birth to relatively small litters (4-25 pups every 3 years). Let’s think about what this means for a moment. A female Mako sharks reproducing and giving birth to a litter for the first time this year would have been born around the year 2001. Can you remember where you were then? This life history characteristic makes these apex predators extremely vulnerable to over-exploitation.

Widespread in temperate and tropical waters of all oceans, they are commercially targeted by fisheries around the world, harvested primarily for their meat and their fins. In addition, their speed and energetic behaviour observed makes them popular amongst sport fishermen, with many Mako shark tournaments taking place in North America every year.

As of today, populations of Shortfin Mako sharks around the world are in decline. The species was recently assessed as Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Shifting the Conversation of Mako Sharks

Shark tourism continues to grow and show fantastic economic potential around the world. Today, shark tourism is a multi-million-dollar industry that supports many economies. In the Bahamas for instance, shark tourism contributes well over US$100 million a year, and represents the largest source of income for the archipelago. Considering the economic potential of keeping sharks alive, it’s no surprise that the nation banned all forms of shark fishing in 2011 and has since become one of the top shark sanctuaries in the world.

But shark tourism offers great opportunities beyond just revenue. Education and first-hand experience have the power to foster a positive shift in the public’s understanding, awareness, attitudes and concern for sharks.

In addition, shark tourism can serve as a great vehicle for research and conservation efforts. The Great White shark population of Guadalupe island, Mexico is a great example. Through daily identification workshops with guests and the raising of funds to support scientific analysis, our Nautilus team was able to identify 366 Great White sharks, and every year we continue to count and identify new individuals on every single trip.

Thanks to ecotourism, scientists and conservationists could gather new insights about Mako sharks, which can in turn inform better conservation and management decisions for the species.

The Path to Sustainability

There already exists several ecotourism platforms that focus on Mako shark encounters in various parts of the world.

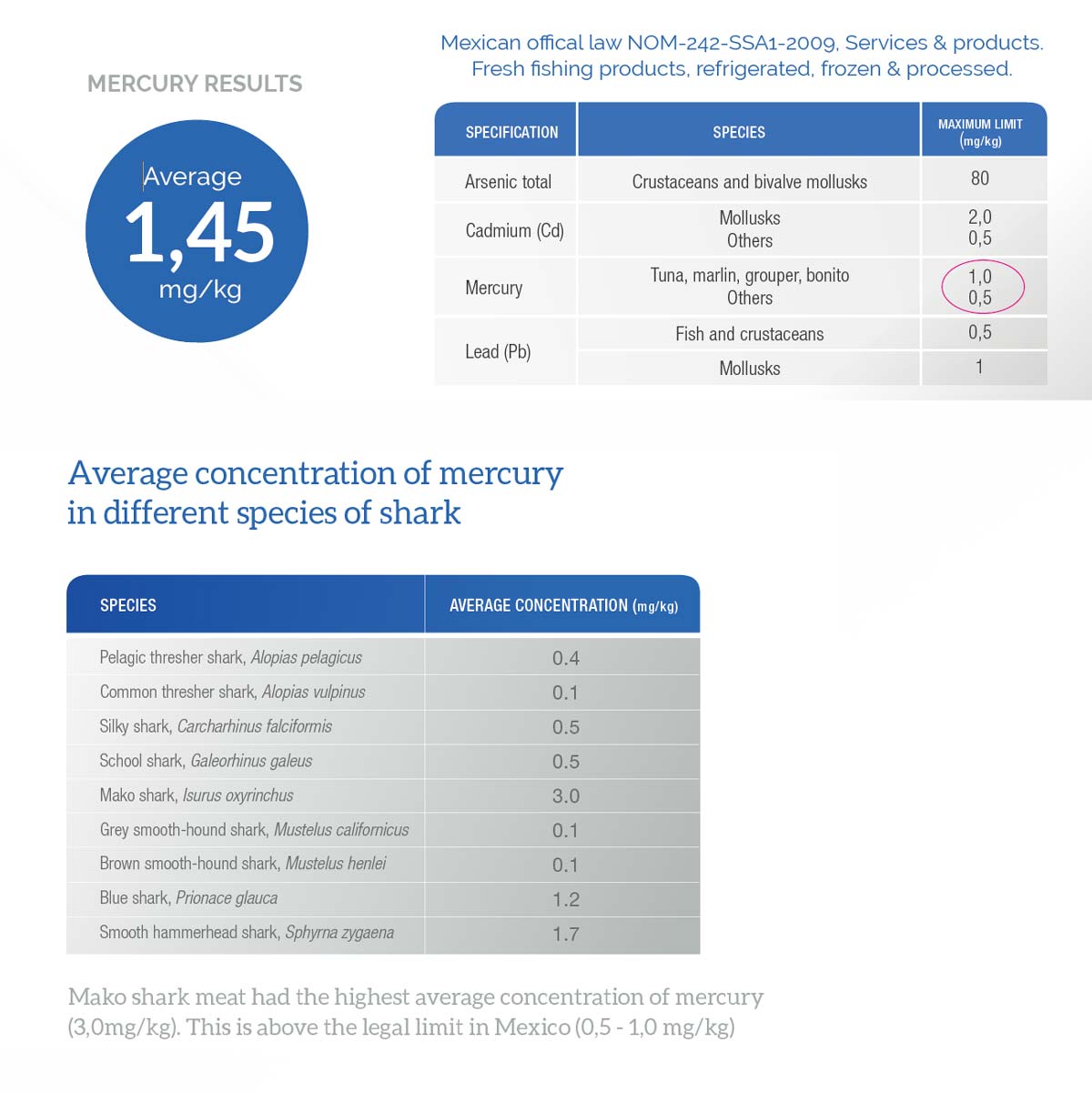

As part of their conservation efforts, Organizations have conducted some research in Mexico over the last couple of years, collecting shark meat for sale in local markets. Shark meat is popular in Mexico and most of the meat is sold under the rather ambiguous name ‘cazón’. DNA testing demonstrated that Shortfin Mako shark is one of the most common species on sale and its meat is often used in fish tacos. According their chemical analysis, they found that methylmercury concentrations in Shortfin Mako shark meat being sold was 3.0 mg/kg. This is three times the legal limit of 1.0 mg/kg.

Why is it a problem? As top predators and fastest sharks in the world, Mako sharks accumulate heavy metals (like mercury) from the large amounts of prey that they consume. Mercury is a neurotoxin. The mercury in their meat is passed on to the human consumer with potentially serious health risks.

From August 17th to August 28th, country representatives from around the world will be attending CITES CoP18 in Geneva, Switzerland, to review and decide on which wildlife species should benefit from greater protection. This year, there is an opportunity to include Mako sharks in CITES’s regulation, which would make the trade of Mako shark products internationally more regulated.